What Is a Real Diamond?

It’s unlikely that you’ll hear a professionally trained gemologist call a diamond a real diamond, or use the word “real” to describe any material. If you want to come across as a smart shopper, you’ll need to rephrase the question.

For decades, diamonds have been the gem of choice for engagement rings. But with the advent of synthetic diamonds and diamond simulants, it’s only natural to ask about real diamonds. “Real” is not a gemological term. But to the consumer, it’s an important one.

A Diamond Is a Diamond Is a Diamond

From a gem professional’s point of view, a diamond is a diamond if it has a characteristic chemical composition and crystal structure. Diamond is composed almost entirely of a single element: carbon. It forms under conditions of high temperature and pressure that cause its carbon atoms to bond in essentially the same way in all directions. Another mineral, graphite, also contains only carbon, but its formation process and crystal structure are very different. The result is that graphite is so soft that you can write with it, while diamond is so hard that you can only scratch it with another diamond.

This definition of diamond applies to diamonds that come from the earth, as well as those that are created in a laboratory. It does not apply to other materials that might masquerade as diamonds.

So, when you ask a jeweler for a real diamond, you could be asking for a diamond created by nature or one created in a lab – since both materials qualify as diamond. Reputable jewelers avoid the term “real” altogether and, following U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) guidelines, clearly distinguish between natural diamonds, synthetic diamonds and diamond simulants (or imitations).

In other posts we explain synthetic diamonds and diamond imitations. Here, we’ll dig a little deeper into natural diamonds and their incredible journey from deep below the earth’s surface to the engagement ring worn by your loved one.

A Brief Description of a Natural Diamond

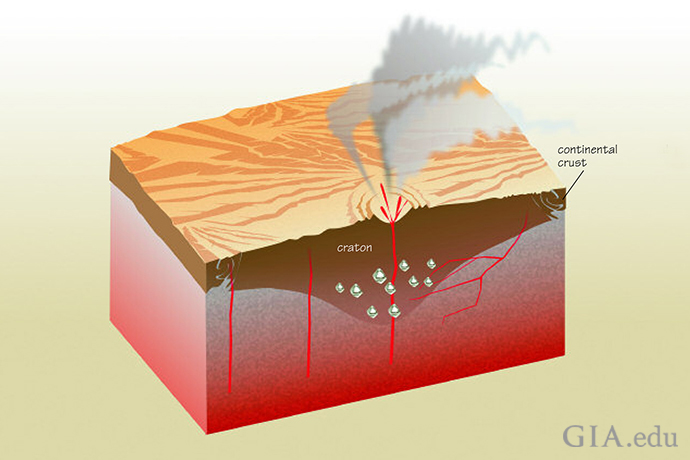

Natural diamonds are one of nature’s wonders. Billions of years old, they formed deep in the earth’s mantle and were brought to the surface by volcanic eruptions. Two types of magma, kimberlite and lamproite, sometimes carried diamond rough with them. The magma quickly solidified into a diamond-bearing kimberlite or lamproite pipe.

A craton is an ancient, deep and stable portion of a continent. Its high heat and pressure provide the right conditions for diamond formation. Conditions under a craton are also stable enough to preserve diamonds for hundreds of millions of years after formation. Illustration: Peter Johnston/GIA

Most of the world’s diamonds are found in kimberlite, but the famed Argyle mine in Australia–once the world’s leading diamond producer– is a lamproite deposit. Major companies recover the diamonds by digging large open-pit mines to find the buried treasures. Over time, as the typically cone-shaped pipes narrow down, the companies switch to underground mining to capture the last of the diamonds.

Some diamonds end up in rivers, streams and even the ocean after forces of erosion released the crystals from their host rocks and gradually washed them into bodies of water. When diamonds are found this way, it’s called alluvial mining – a process of digging and sifting through mud, sand and gravel. While river sediments are often worked by small-scale miners using rudimentary techniques, large boats are used to scour the ocean sands off the coast of Namibia in search of fine diamonds.

Natural diamond rough is often shaped like an octahedron. Photo: Robert Weldon/GIA. Courtesy: Fusion Alternatives

For most of recorded history, the extreme scarcity of diamonds made them available only to the elite. In fact, up until 1730, the Golconda region of southern India and the Pacific island of Borneo were the only known diamond-producing regions in the world. Then diamonds were discovered in Brazil around the 1720s and a diamond ‘rush’ began. Soon, Brazil eclipsed India as the world’s top diamond producer, holding this title through the mid-1800s. With the discovery of large diamond-bearing kimberlite pipes in South Africa in the late 1860s, mining began on an industrial scale, increasing supply to meet broader consumer demand. Diamonds are now mined in several countries around the world, including Russia, Botswana and Canada, as well as South Africa and Australia. Learn more about where diamonds come from.

The face-up view of this diamond showcases the beauty of the round brilliant cut. Photo: Robert Weldon/GIA. Courtesy: Rogel & Col, Inc.

Turning Rough Diamonds into Polished Gems

The diamonds recovered have survived a brutal birth and then a rough ride to the earth’s surface. Diamond mining companies must remove a million parts of host rock to find one rough diamond. Workers then sort the rough diamonds into categories based on their size, shape, clarity and color. The mining company might cut a finished diamond out of the rough, or sell it to dealers and manufacturers.

Rough diamonds are often shipped to cutting centers in India, Israel, New York, Antwerp, China and Thailand. Highly skilled diamond cutters often use the latest technology, such as lasers, to transform the piece of rough into a highly polished faceted diamond. Most finished diamonds are sent to grading laboratories to determine their quality based on the GIA 4Cs standard: color, clarity, cut and carat weight. Every diamond will have unique qualities: no two will be identical.

A diamond cutter at Diacore Botswana examines the initial facets made on a fancy yellow diamond. Photo: Robert Weldon/GIA

Diamond Treatments

Some manufacturers may try to alter the color or clarity of a diamond to make it more appealing and marketable. The methods used to alter color range from crude ones like coloring girdle facets with a permanent marker, to more sophisticated ones like covering facets with an optical thin film, subjecting the diamond to radiation, or exposing it to high pressure, high temperature annealing. The most common clarity enhancement is fracture filling. All of these may improve the appearance of the diamond, but the seller is legally bound by the FTC to disclose that the diamond has been treated.

This 1.05 ct diamond owed its apparent Fancy Light brown-pink color (left) to a coating. After the coating was removed by acid cleaning, the diamond was given a color grade of J (right). Photo: Jian Xin (Jae) Liao/GIA

Given their timelessness, resilience and durability, is it any wonder so many choose ”real” diamonds as a symbol of love and commitment? If you’re considering a natural diamond for an engagement ring, be sure to ask for a GIA Diamond Grading Report . The report is your proof that the diamond is natural and that its quality is what the seller describes, giving you the important information you need to make your purchase with confidence. And if you opt for a lab-grown diamond, a GIA Synthetic Diamond Grading Report is your assurance that the material is actually diamond and not an imitation.

Have you ever wondered about do-it-yourself tests to determine whether a specific gem is natural, synthetic or something else? Our post, How to Tell if a Diamond is Real, decodes the most common myths about such tests and why they don’t work.